CHURCH ARCHITECTURE IN COLONIAL AUSTRALIA

AN OVERVIEW

By Walter Phillips

Emeritus Scholar

La Trobe University

Melbourne

When Australia was first settled by the British in 1788 the prevailing architectural style in England was Georgian; and this was mostly the style of architecture of the churches built in New South Wales and Tasmania up to the late 1830s. The first churches built in the first decade of the nineteenth century –St John’s Parramatta and St Phillip’s1 Sydney- were constructed in a crude Georgian. St Phillip’s featured an incongruous round tower for which it was dubbed ‘the ugliest church in Christendom’. Twin towers with spires were added to St John’s in 1818-19. Christ Church, built in Newcastle in 1817 with a tall spire that had to be pulled down in 1820, was not strictly Georgian, having ogee arched windows and doors, but it was of similar dimensions to St John’s and St Phillip’s. None of these early churches are still standing, apart from the towers of St John's which were incorporated into the large Norman style church built on the site in the 1850s. The simple, solid Ebenezer Church erected at Wilberforce in 1809, having some Georgian features, survives as the oldest church building in Australia.

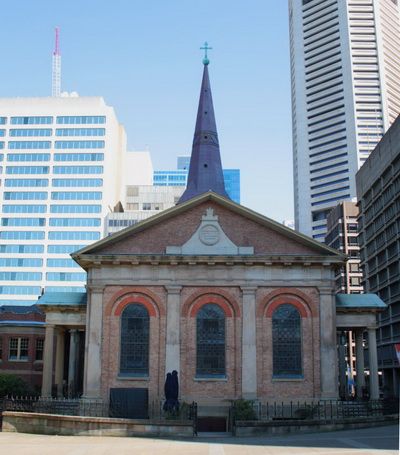

Professional church building began with Francis Greenway, an architect from Bristol transported to New South Wales for forgery in 1814. Greenway set up in practice in Sydney and in 1816 Governor Macquarie appointed him Civic Architect. He designed a number of handsome Georgian buildings, the best known Hyde Park Barracks in Sydney (1817). He also designed an elegant Georgian church in brick, St Matthew’s Church, Windsor (1817), recognised as his masterpiece, as well as St Luke’s, Liverpool (1818) and St James’s Church, Sydney (1821). These three churches are still standing, with some alterations.2

Georgian churches generally had a broad rectangular nave with large rounded or squared windows with small panes. They might feature an apse at the liturgical ‘east end’. Ceilings were usually flat and ornamented. They mostly had towers without a spire, in some case crenellated, in others with a domed top. St James’s, Sydney is one of the few with a spire, although some late Georgian churches in England had spires. Internally, the Georgian church generally did not have a central aisle. They were designed as auditories, with box pews, and the three-decker pulpit, as in eighteenth century churches in England, sometimes in a central position, but mostly off-centre in Anglican churches.

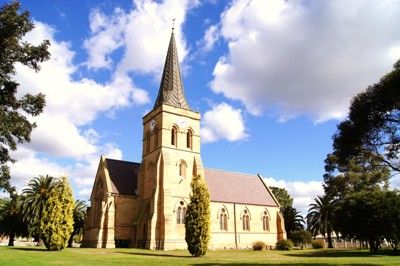

Several churches were also built in the Georgian style in Tasmania, where some are still in use, notably St George’s Battery Point in Hobart (1836, 1841-47) and St Luke’s, Richmond (1834), both designed by John Lee Archer. James Blackburn, who designed additions to St George’s, also designed several churches in Neo Norman or Romanesque, particularly St Mark’s Anglican Church, Pontville (1839) and a handsome Classical Revival Presbyterian Church at Evandale (1839-40).3

St Jame’s Church Sydney built in 1821.

Designed by Francis Greenaway

The Georgian style was going out of fashion at the time South Australia and the Port Phillip District of New South Wales (Victoria from 1851) were settled. However, St James’s Cathedral in Melbourne was built in the Georgian style (1839-42) and survives, but not on its original site and with some alteration. Some smaller Georgian churches were built in Victoria and survive, mostly as church halls.4

Antiquarianism and the Romantic movement in the later eighteenth century stimulated an interest in Gothic architecture, despised by classicists. Some churches in Australia were also built in a free Gothic style, with rectangular naves of Georgian proportions, the main feature being pointed windows and central towers, such as Scots Church Sydney (1824) and St John’s New Town, Tasmania (1835). St John's, Camden, New South Wales (1840-49) is more decisively Gothic but is rather more 'picturesque', than a Gothic Revival church.

The Gothic Revival began with Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, born in 1812. Pugin converted to Roman Catholicism in 1835 and fell in love with the Gothic architecture of the late medieval period. In 1836 he published his views in Contrasts, or a Parallel between the Noble Edifices of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries and Similar Buildings of the Present Day; showing the Present Decay of Taste, a polemical but persuasive piece which established his reputation. But for Pugin Gothic was more than a matter of taste. It had a religious value above all other styles, as he explained in the True Principles of Pointed or Christian Architecture published in 1841. He believed that the revival of Gothic architecture in churches would lead to the revival of faith in England. He opposed it to styles he condemned, Classical and Georgian, as ‘pagan’, examples of Protestant bad taste.

4.Pugin emerged at an opportune time for Catholics in England. Following Catholic Emancipation in 1829 Catholics were free to build churches without the limitations of the Catholic Relief Act of 1791, which gave them freedom of worship but restricted the kind of chapels they could build no bells or spires and no public display of the Catholic religion.

St Luke’s Richmond Tasmania 1834.

Designed by John Lee Archer

Pugin designed many churches in Britain up to his death in 1852. He also designed some for Catholic bishops in New South Wales and Tasmania. He won other architects to his religion and to his principles. Some of them also designed churches for Australia, notably Charles Francis Hansom who was the architect of a number of Catholic churches in Victoria, a few in New South Wales, and of St Francis Xavier's Cathedral in Adelaide, in all instances constructed under the supervision of local architects. One of Pugin's followers in Tasmania, Henry Hunter, designed some fifty churches in that colony, including a few Anglican churches.

William Wilkinson Wardell, born 1823, was a convert to Catholicism and a pupil of Pugin, who designed a number of churches in England before arriving in Melbourne in 1858, in time to save the projected St Patrick's Cathedral from disaster. Wardell proposed a cathedral of magnificent proportions in bluestone, blending French Gothic with English. St Patrick's is generally regarded as his masterpiece. As well he designed many churches in Melbourne and country Victoria, almost all Roman Catholic; one exception is St John's Anglican Church, Toorak, which he designed without a fee. He also designed St Mary's Cathedral in Hobart, supervised and modified by Henry Hunter. Following the fire which destroyed the old St Mary's Cathedral in Sydney, Archbishop Polding invited Wardell to design a new cathedral for Sydney. He designed another great Gothic cathedral in sandstone.

Another impetus in the Gothic Revival came from a group of Cambridge undergraduates who began to study church architecture in the late 1830s, perhaps stimulated by Pugin's Contrasts. In 1838 they formed the Cambridge Camden Society to promote their principles and in 1841 they launched the Ecclesiologist, a periodical which featured and discussed plans for churches and their furnishings. The same year the Society published A Few words to Church Builders, written by John Mason Neale, one of its founders. It maintained that the essential requirements of a Christian church were a nave and a long chancel. Like Pugin, the Society regarded Gothic as the only Christian architecture; it regarded the fourteenth century Decorated as the acme of the Gothic style. It looked on Perpendicular Gothic with disdain, and was dogmatic in its prescriptions. Like Pugin, the 'Ecclesiologists' thought that the adoption of Gothic would lead to the revival of religion, in their case the true Anglican faith.

St Patricks Cathedral East Melbourne

Designed by William Wilkinson Wardell in 1858.

The Georgian churches were the antithesis of all that the Ecclesiologists stood for. They abhorred the three-decker pulpit and box pews and satirised the Georgian church in cartoons. They opposed the 'auditory' church and made the altar or Holy Table the focus of worship. Unlike the contemporary Oxford Movement they were not primarily interested in theology but in the theatre for worship. However, they shared with the Oxford Movement the emphasis on the Catholic heritage of Anglicanism and won the support of many Anglo-Catholics. The Society enjoyed wide support in the 1840s with the two archbishops and other bish-ops and clergy among its membership as well as architects.

The Camden Society held that the architects of Gothic churches should be Christians sharing their ideals. Some such archi-tects designed churches for Australia, notably William Butterfield, who designed St Peter's Cathedral in Adelaide and St Paul's in Melbourne. Richard Cromwell Carpenter's design for St John the Baptist in Cookham Dean, Berkshire was fea-tured in the Ecclesiologist as an appropriate model for small churches in the colonies; it was copied and adapted for St John the Baptist's Church, Prosser's Plains (now Buckland), Tasmania (1846-48) and Holy Innocents, Cabramatta, (now Rossmore) , New South Wales (1848-49). Another Carpenter design was employed with modifications by Henry Hunter in St Mary's Church, Hagley, Tasmania (1861-71). John Loughborough Pearson, a later member of the Society, designed St John's Anglican Cathedral in Brisbane (1887-89). It was constructed to a revised design by his son, Frank Loughborough Pearson (1901-10, 1964-68, 1989-2009). Pearson senior's design for a cathedral in Grafton was not executed.

George Gilbert Scott ( later Sir Gilbert) was another architect who began working in Gothic, influenced initially by Pugin. However, in 1841 he designed the famous Protestant Martyrs Memorial in Oxford, something which outraged Pugin.

Scott joined the Cambridge Camden Society in 1842, although he had an uneasy relationship with the Society over the years. The Ecclesiologist general-ly approved Scott's design of St Giles's Church, Camberwell (1842) though not without some neg-ative criticism. However, it was appalled when he won the design for the rebuilding of the Nicholai-Kirche in fourteenth century German Gothic in Hamburg in 1845. Gothic was reserved for those who kept the true faith! Scott continued design-many churches, but also devoted much of his time to the restoration of Gothic churches and cathe-drals. He designed one church for Australia, St Alban's Muswellbrook, in 1863, constructed un-der the supervision of Horbury Hunt (1863-69), at the time an associate of Edmund Blacket who gave him the job. Several architects in Australia claimed to have been pupils of Scott, particularly Nathaniel Billing in Victoria.

St Albans Muswellbrook

The leading Gothic Revivalist in Australia was Ed-mund Thomas Blacket, whose work was done mainly in New South Wales. Trained as an engi-neer and a skilled draftsman, Blacket had no for-mal architectural training. He did, however, spend a year sketching English medieval architecture, although he does not seem to have had any acquaintance with the Cam-den Society. He arrived in Sydney in 1842 where he assumed the role of architect and eventually set up in practice. He had an introduction to Bishop Broughton

who appointed him diocesan architect. In 1849 he was appointed Colonial Architect in succession to Mortimer Lewis in 1849. He resigned in 1854 when he was appointed to design buildings for the newly established University of Sydney. Several colonial architects trained in his office and others came to join him. He won a number of commissions for numerous churches in the Gothic style in New South Wales and one, Christ Church, Geelong, in Victoria. He designed a new church in perpendicular Gothic to replace the old St Philip's on Church Hill, Sydney, in 1848, and completed the abandoned work on St Andrew's Cathedral incorporating it into a new design. Blacket also designed cathedrals for dioceses in New South Wales as well as Queensland and Western Australia, namely: All Saint's Bathurst Church, later Cathedral, in Norman style (since demolished); St Saviour's, Goulburn in Decorated Gothic (1874-84) incomplete; St George's Cathedral Perth, designed 1878 and constructed in brick (1879-88) without Blacket's supervision. St James's Cathedral, Townsville, sometimes attributed to Blacket, was designed by his son Arthur in 1885. It was partly constructed, in brick (1887-1903) and finally completed (1953-1960).

Blacket, like Butterfield, was brought up in English Dissent and became a High Anglican. Religious conviction underlay his designs in Gothic but opinions differ as to the originality of his designs. Some have seen him as the Wren or Pugin of Australian church architecture, but Morton Herman sees an unevenness in his work and in his entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography H.G. Woffenden states that Blacket 'put tradition before innovation and in doing so rarely committed errors of taste'. He left a great legacy in many handsome churches but also the impression that church building was 'as an entirely antiquarian endeavour'.

Among the architects employed in Blacket's practice was John Horbury Hunt. He came from a very different background. Born in Canada and trained in the United States, he was persuaded to remain in the colony when he visited in 1863. He joined Blacket and became his chief assistant, supervising the church at Muswellbrook, mentioned above. Hunt left Blacket in 1869 and, after a brief part-nership with John Frederick Lilly, he set up on his own. Innovative and individu-alistic Hunt produced much interesting domestic architecture as well as designing several Gothic churches in country New South Wales, including three cathedrals in brick: St Peter's Armidale, opened in 1875 and consecrated 1886; Christ Church Cathedral in Grafton, consecrated in 1884; and Christ Church, Newcastle, designed in 1875, but not built until the 1890s and opened and dedicated in 1902. One of Hunt's last commissions was the chapel of the Sacred Heart Convent, Rose Bay. Hunt's churches did not meet all the stipulations of the Ecclesiologists. His churches generally had a a shallow nave and they are less ornamented with cleaner lines, with overhanging roofs; but impressively gothic nonetheless.

St Matthias built 1874. Architect Horbury Hunt.

While the influence of the Gothic Revival in Australia was mainly on Anglican and Catholic church design in the second half of the nineteenth century, other denominations gradually turned to Gothic, but not from the same principles that guided the followers of Pugin or the 'Ecclesiologists' of the Camden Society. The Methodist and the denominations descended from English Dissent did not need narrow naves and long chancels. The Dissenting Meeting Houses followed the dictum of Christopher Wren, that Protestant churches should be designed principally as 'auditories'. They were rectangular with a central pulpit, a two decker with a sounding board above it, on the long wall facing the pews and often a gallery around the other three walls. The communion table and communion pew were in front of the pulpit. Outwardly the meeting house was plain but dignified, and not usually built in prominent places. With the repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts in 1828 the Dissenters were free to come out of hiding and build chapels, as they now called their places of worship, wherever they could and in whatever style they chose.

They did not immediately turn to Gothic. Meeting houses were either rebuilt or demolished, as Nonconformists began to build new chapels in classical Greek style, or in some places more expensive Italianate styles. They slowly turned to Gothic. Ironically, probably the first Nonconformist chapel built in the Gothic style in England was Highbury Congregational Chapel (1843) in Bristol, designed by the Gothic Revivalist, William Butterfield, in Perpendicular Gothic, financed by W.D. Wills of tobacco fame. Butterfield got this, his first commission through his father's Congregational connections. Butterfield is alleged to have said he regretted building a 'schism shop'. He may rest in peace as the chapel is now an Anglican Church!

The earliest chapels of Methodists and other Protestants in Australia were often built in the classical or Georgian style. The Wesleyan Methodists in Sydney built a solid classical style church in York Street in 1838 to mark the centenary of John Wesley's evangelical conversion. In Melbourne two years later the Wesleyans began building a new chapel on Queen Street, designed by John Peers, a builder more than an architect. According to J. M. Freeland, architecturally it was hybrid. 'Basically a simplified Regency style, it had the outward and visible symbols of Gothic...' The second Scots (Presbyterian) Church erected on Collins Street designed by Samuel Jackson, a builder, in 1841, was tentatively Gothic. In 1857 the architect Charles Webb designed a tower and spire in Gothic Revival style, and renovated the whole church. A little over a decade later it was found to be unsafe. It was replaced in 1872-73 by a large church in Decorated Gothic 'with a spacious nave and sloping floor' and gallery designed by Reed and Barnes. It also has a tower with a tall spire to match the Congregational church on the opposite corner.

Scots Presbyterian Melbourne

Designed by Samuel Jackson, in 1841

The Classical style was still preferred by some in the 1840s, particularly by the Baptists. John Bibb, formerly assistant to John Verge, an exponent of Greek Revival designed the Baptist chapel in Sydney in Classical style. In 1846 Bibb designed the new chapel for Congregationalists in Pitt Street Sydney in Greek Ionic style. Regarded as the most important of this architect’s work, the building was later enlarged and altered but ‘in complete harmony’ with Bibb’s original design. The best example of Classical Architecture in Melbourne is Collins Street Baptist Church in Melbourne, built 1845 and enlarged with a Corinthian style portico by Joseph Reed (1861-62).

The first serious attempt at Gothic by the so-called Nonconformists in Australia was Wesley Methodist Church in Lonsdale Street, Melbourne. There was some opposition to the Gothic style because of its association with ‘popery’. Designed by Joseph Reed in Decorated Gothic and constructed 1857-58, Wesley was a landmark in Nonconformist colonial Gothic. Internally, Wesley was more like a stylish meeting house, with a high central pulpit overshadowing the communion table, and with galleries around three sides. Recent alterations have made it more cathedral-like, but the galleries remain. Wesley also represented a move from chapel to church, a deliberate name change. Ironically, one of the reasons given that chapel had ‘popish’ associations! This change of name was soon generally adopted by Nonconformists. After the erection of Wesley Church almost every Wesleyan Methodist Church in Victoria to 1900 was built in the Gothic style. One notable exception is the Wesleyan Church at Portland, built in Renaissance style in 1865. The Primitive Methodists and Bible Christian were slower to adopt Gothic.

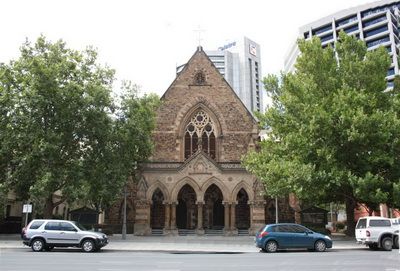

There was some resistance to Gothic among Congregationalists, particularly from James Jefferis, first minister of the Brougham Place Congregational Church, North Adelaide. As a student Jefferis had been impressed by the magnificence of Gothic cathedrals and moved by the music in them, but by the time he came to Adelaide he was an ardent advocate of ‘the Grecian style’ which he considered better acoustically and more suited to Protestant worship, and to the Australian climate. In his brief pastorate in the Italianate model village in Saltaire, Yorkshire, he had watched the building of a beautiful Italianate Church, which probably influenced him towards this style. The architect, Edmund Wright, also believed that the Italianate style was more suitable to the South Australian climate. He designed the Venetian Ionic style church built on Brougham Place in (1860-61).

At this time there were other voices from English Congregationalist architects looking for an architectural style based on a theory that would provide an alternative to the theories of the Ecclesiologists of the Camden Society.

Example of Italianate style.

Congregational (Uniting) Church, North Adelaide

Designed by Edmund Wright

Jefferis seemed unaware of them, but the Reverend A.M. Henderson, who became minster of Collins Street Independent Church in 1866 was aware of the literature published in Congregational journals. The old Georgian chapel was demolished that year to make way for a new and larger church. The architect Joseph Reed presented two designs. The first in Gothic and the second in Romanesque, to meet the acoustic requirements Henderson insisted on. Instead of a central pulpit it had a platform to give the more freedom to the preacher to move about for dramatic effect. Now known as St Michael's Uniting Church, this unique building in polychrome brick with a tall campanile became a landmark in Melbourne. Alfred Dunn, a promising young architect, designed a similar church to St Michael's in Hawthorn, Victoria: a Wesleyan church, built in polychrome brick in American Romanesque in1888-89. Like St Michael's it has excellent acoustics, and has been regarded as the finest Wesleyan Church in Victoria. Now known as Auburn Uniting Church, it remains one of outstanding churches of the nineteenth century in Victoria.

These two churches, however, were exceptions to the trend toward Gothic among 'Nonconformists'. Gothic was becoming the proper architecture for churches of virtually all denominations. Its acceptance among 'Nonconformists' was eased to some extent by the writings of John Ruskin, namely, The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849) in which he defended Gothic as the noblest form of architecture, and The Stones of Venice (1851-53), in which he exalted the Gothic architecture in Venice and excoriated the Renaissance style. As an Evangelical Protestant Ruskin's promotion of Gothic, was free of Roman Catholic or Anglo-Catholic overtones. But James Jefferis claimed to have read Ruskin and remained unconvinced. Not all Jefferis's fellow Congregationalists in Adelaide, however, were convinced by him.

When in 1864 the members of the Freeman Street Congregational Chapel were considering plans for a new church to be named in honour of their founding minister, Thomas Quinton Stow, they invited Jefferis to talk to them on 'The Desirable and Undesirable in Church Architecture'. He conceded the impressiveness of Gothic and the associations it carried, but suggested that it did not measure up to the criterion he stated the nature and necessities of Christian worship'. In his opinion, the Grecian style had 'a chaste sim-plicity' and was eminently suitable 'for clear and distinct enunciation' in contrast to the 'dim religious echo' heard in other styles. But the building committee accepted the design for a Gothic church by Robert George Thomas.

Thomas was one of the original colonists in South Australia and worked with the Government Surveyor, the architect George Strickland Kingston, for several years before forming a partnership with William Parry James. They returned to England in 1846 and practiced for some years in Newport Wales, where Thomas designed a number of buildings including chapels, principally in Gothic style. He returned to Adelaide in 1861 and received his first commission to design the Flinders Street Baptist Church. His brother, a deacon of the Church, might have assisted him in obtaining this commission.

Flinders Street Baptist is a striking Gothic building, most unusual for the Baptist denomination. Thomas described the church as a building in 'early Gothic, with details somewhat continental and Italian in character, although plain and unpretending'.

St Michael’s Collins Street Melbourne

Architect Joseph Reed.

Built in polychrome brick, 1866.

It has a central pulpit and stage with no central aisle and a gallery on three sides, as with most Nonconformist churches of the time. Built in 1861, it stood as a possible example to the Congregationalists planning their new church.

Thomas designed Stow Memorial Church (now Pilgrim Church) in 'an eclectic mixture of Early English, Decorated and French [Gothic] and sui generis', with a tower and spire on the east side. This was never built. The nave has a sloping floor and had a central aisle in the nave as far as the transepts. The pews in the crossing stretched across with aisles at each end. Originally, the church had a central pulpit. During alterations in 1908 the central pulpit was removed creating a platform on which the communion table rested and an elegant goblet pulpit was erected off centre. More recent alterations have completed the transformation of the interior from a Nonconformist style to a cathedral-like interior, with a full length central aisle suitable for processions.

Notwithstanding these two impressive gothic churches designed by Thomas, architectural styles were more diverse in Adelaide than in other cities. The Congregational Church in Hindmarsh Square was built in 1862 in a modified Byzantine style. R.G. Thomas designed the Alberton Baptist Church in Italianate style 1862. Several large churches were built in Renaissance style: Flinders Street Presbyterian (1863-65), since demolished; St Ignatius Catholic Church, Norwood (1870); Norwood Wesley, 1877 (now Russian Orthodox); Glenelg Congregational (1880), now Uniting Church. The Primitive Methodists built an imposing Classical style Church in Wellington Square, North Adelaide in 1882.

There were many Lutheran Churches in South Australia, particularly in the Barossa Valley, mostly in German Gothic style with towers and steeples. Trinity German Lutheran Church in East Melbourne was designed by Charles Blachmann (later Anglicised to Blackmann), who worked for a time in the Victorian Public Works Department under the Colonial Architect W.W. Wardell, and later moved to Sydney where he practiced as an architect.

Pilgrim Church Adelaide, example of Early English,

decorated and French [Gothic] style.

By Thomas Quinton Stow

Trinity may have been the only church he designed. Built in Early English Gothic the church may also have German antecedents. It has no central aisle and has a sloping floor, like many of the ‘Nonconformist’ Gothic churches.

By the close of the nineteenth century the Gothic style was dominant in Australia, notwithstanding the exceptions mentioned above. Even the wood and iron churches in the bush had pointed windows. When the cathedral for Townsville was being planned in the late nineteenth century, Morton Herman comments: 'Such are the rigours of fashion that in sweltering Townsville it was unthinkable to have anything but a Gothic cathedral of a type evolved to suit northern Europe with its bitter frost-bound winters'.

The Gothic Revival in Australia was sustained partly by love of the style and the associations of 'home' it bore for many; and by the conviction of some that this was the Christian architecture. But it was also driven by denominational competition. For Roman Catholic bishops a large Gothic cathedral made a public statement about the Catholic faith to the community at large, even if it put a great financial burden on the faithful. As the building of St Mary's Cathedral progressed in Sydney the Catholic Freeman's Journal proclaimed that its splendour and prominence would daily remind the world that 'it represents the Christianity of New South Wales', clearly marking 'the contrast between the sects and the Church'. Anglicans had to compete by building their own grand cathedrals and churches. The other denominations could not be out built, especially as their congregations grew in wealth and respectability. They wanted to build churches that people would 'not be ashamed of attending'. They wanted their places of worship to look like 'proper churches', not to be confused with banks of post offices, and that meant Gothic. (But some banks and other public buildings were also adopting the Gothic style!)

But changes in style were coming in the late nineteenth and into the early twentieth century. Not all Catholics agreed with Pugin on the Gothic style. Cardinal Newman, who thought Pugin was 'a bigot' on the matter of architecture, had the Brompton Oratory (1880-84) built in Italian Renaissance style; and Westminster (Catholic) Cathedral, London (1895-1903) is in a Neo-Byzantine style. Catholic churches in Adelaide and Melbourne were built in Renaissance or Romanesque around this time: Sacred Heart, St Kilda (1884); Sacred Heart, Carlton, (1897); St Patrick's, Grote Street, Adelaide (1913-1914) in Renaissance; and the Presbyterian Church, Glenferrie Road, Hawthorn (1891); St John's East Melbourne, (1900 and 1930);) St Raph-ael's, Parkside, Adelaide (1916): Our Lady of Victories, Camberwell (1913-18) in Romanesque–all large and impressive churches. Some churches were built in Gothic in the twentieth century and some built in the nineteenth century were completed with the erection of spires. Although styles in church architecture were more diverse in the twentieth century the Gothic churches of the nineteenth century remained outstanding features in towns and countryside

St Patrick’s, Grote Street, Adelaide

Example of Renaissance style

© 2012: Dr Walter Phillips, Emeritus Scholar, La Trobe University

No part of this Overview can be copied or reproduced without express permission.

References

- Joan Kerr [and] James Broadbent, Gothick Taste in New South Wales, Sydney, The David Ell Press, 1980, pp. 38-40; James Jervis, A Short History of St. John’s Parramatta, James Jervis, 1963, pp.5-13

- Max Dupain and others, Georgian Architecture in Australia: with some examples of the post Georgian period, Sydney, National Trust of Australia (NSW), 1973

- Douglas Baglin [and] Barry Thiering, Australian Churches, Sydney, Ure Smith,1979, pp.38, 68; Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol.1,pp.109-10

- Dupain, Georgian Architecture, passim; Victorian Churches, Ed Miles Lewis, Melbourne, National Trust of Australia (Victoria), p.46 and passim Kerr, Gothick Taste. 124

- 5. Phoebe Stanton, Pugin, London, Thames and Hudson, 1971;Brian Andrews, Creating a Gothic Paradise in the Antipodes, Hobart, Tasmanian Museum & Art Gallery, 2002,pp. 3-13

- Brian Andrews, Australian Gothic: the Gothic Revival in Australian Architecture from the 1840s to the 1950s, Melbourne, Melbourne University Press, 2001, pp.146-48, 151-53; Andrews, Creating a Gothic Paradise, pp. 227-29 On W.W. Wardell, see Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol.6, pp. 354-55; P.J. O'Farrell (ed) St Mary's Cathedral Sydney 1821-1971, Sydney, Devonshire Press, 1971; Walter Ebsworth, St Patrick's Cathedral, Melbourne, Revised Edition, Mel-bourne, H.H. Stephenson, 1979

- Christopher Webster, "'Absolutely Wretched': Camdenian Attitudes to the Late Georgian Church" in 'A Church as it should be': The Cambridge Society and its Influence, Eds Christopher Webster and John Elliott, Stamford, Shaun Tyas, 2000, pp.1-21

- See Andrews, Australian Gothic, pp. 143-55

- Gavin Stamp. 'George Gilbert Scott and the Cambridge Camden Society', in 'A Church as it should be', pp. 180-82; Victorian Churches, pp.22,23

- Morton Herman, The Blackets: An Era of Australian Architecture, Sydney, Angus and Robertson, 1963, passim 13 Ibid. p.167; Australian Dictionary of Biography, Vol. 3,pp.173-75

- J.M. Freeland, Architect Extraordinary: The Life and Work of John Horbury Hunt: 1838-1904, Mel-bourne, Cassell Australia,1970, chapters 3-6; Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol. 4, p.447

- Kenneth Lindley, Chapels and Meeting Houses, London, J. Baker, 1969

- Christopher Stell, 'Nonconformist Architecture and the Cambridge Camden Society' in 'A Church as it should be'. p. 322

- J.M. Freeland, Melbourne Churches 1836-1851, Melbourne, 1963; Victorian Churches, p.45

- Susan Emilsen and others, Pride of Place. A History of the Pitt Street Congregational Church, Melbourne Publishing Group, 2008, pp.50-52; Victorian Churches, p.46

- C. Irving Benson, A Century of Victorian Methodism, Melbourne, Spectator Publishing Co., 1935, pp.125-26

- W. Phillips, James Jefferis: Prophet of Federation, Melbourne, Australian Scholarly Publishing, 1993, p40; Australian Dictionary of Biography, Supplement, 414-15

- Christopher Wood and Mark Askew, St Michael's Church: Formerly the Collins Street Independent Church, Melbourne, Melbourne, Hyland House, 1992, pp.59-61

- Victorian Churches, p.74

- Phillips, James Jefferis, p.40

- Observer (Adelaide), 30 January 1864; Phillips, James Jefferis, Australian Scholarly Publishing, 1993, p.40

- Brian Andrews, Gothic in South Australian Churches, Adelaide, The Flinders University of South Australia, 1984, p.22

- Ibid., p.27; [Ray Beanland, Grant Dunning] ‘An Historical; and Architectural Guide to the Pilgrim Church Adelaide’, Brochure, nd.

- See John Whitehead, Adelaide: City of Churches, Adelaide, M.C. Publications, 1986, passim

- Herbert D Mees, A German Church in the Garden of God, Melbourne, Aki Historical Society for Trinity German Lutheran Church, 2004), pp. 448-63

- Morton Herman, The Blackets, p. 200

- Cited in W. Phillips, Defending "a Christian Country": Churchmen and Society in New South Wales in the 1880s and after, St Lucia, University of Queensland Press, 1981, pp 43.44

- Presbyterian (Sydney), 28 November 1885; Australian Christian World (Sydney) 18 June 1886; Wesleyan Chronicle (Melbourne) February 1867, quoted in Renate Howe, 'The Wesleyan Church in Victoria, 1855-1901: Its Ministry and Membership' MA Thesis, University of Melbourne, 1965,p.9; Daily Telegraph (Sydney), 19 October 1885

- Stanton, Pugin, p.7